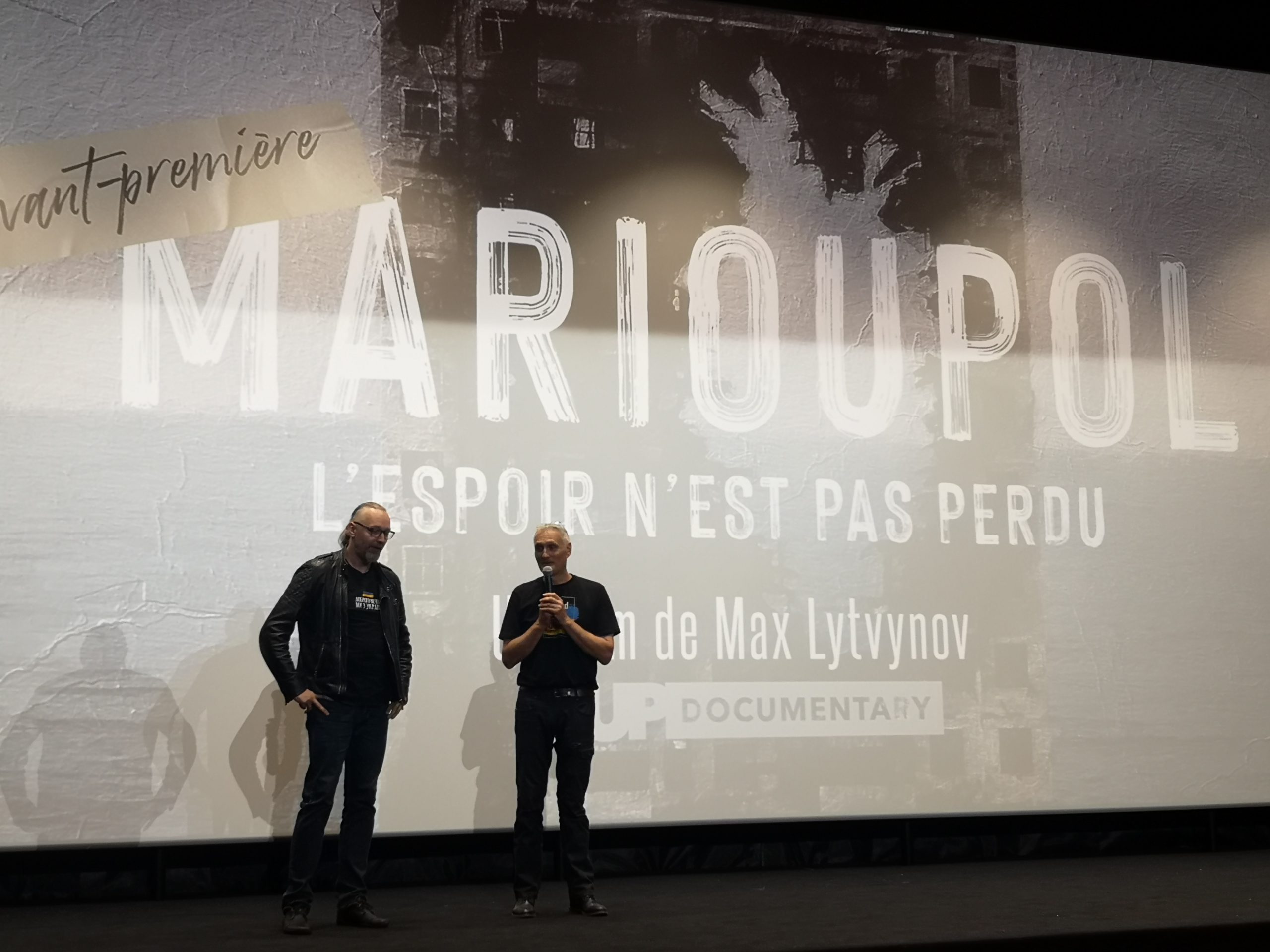

Campaign For Empathy. How the World Watched OUP´s Film “Mariupol. Unlost Hope”

“Everybody should watch it,” a Czech viewer whispered to me after the lights switched on in Brno cinema hall. He whispered not to break the silence. ‘Cause the audience left the hall silently, several people wiped tears.

All the screenings organizers recall this moment of silence in the first moment after the film ends. “Deep silence! The audience sits stunned, dumbfounded. No one moves or breathes. I hear only sobbing and paper napkins rustling. Emotions are so strong, so deep that even applause would be inappropriate,” describes Stefané Dalmat, the French screenings organizer. — “For a few minutes I pay tribute to this sacred moment of reflection and feelings. Then I quietly break the silence and start a discussion.”

When we, in the Organization of Ukrainian Producers (OUP), ideated this global campaign for empathy, we wanted to create at the end a reel with viewers impressions. Now I understand why this idea failed: it’s hard to approach a person in such a mood with a camera.

Cities similar to Mariupol

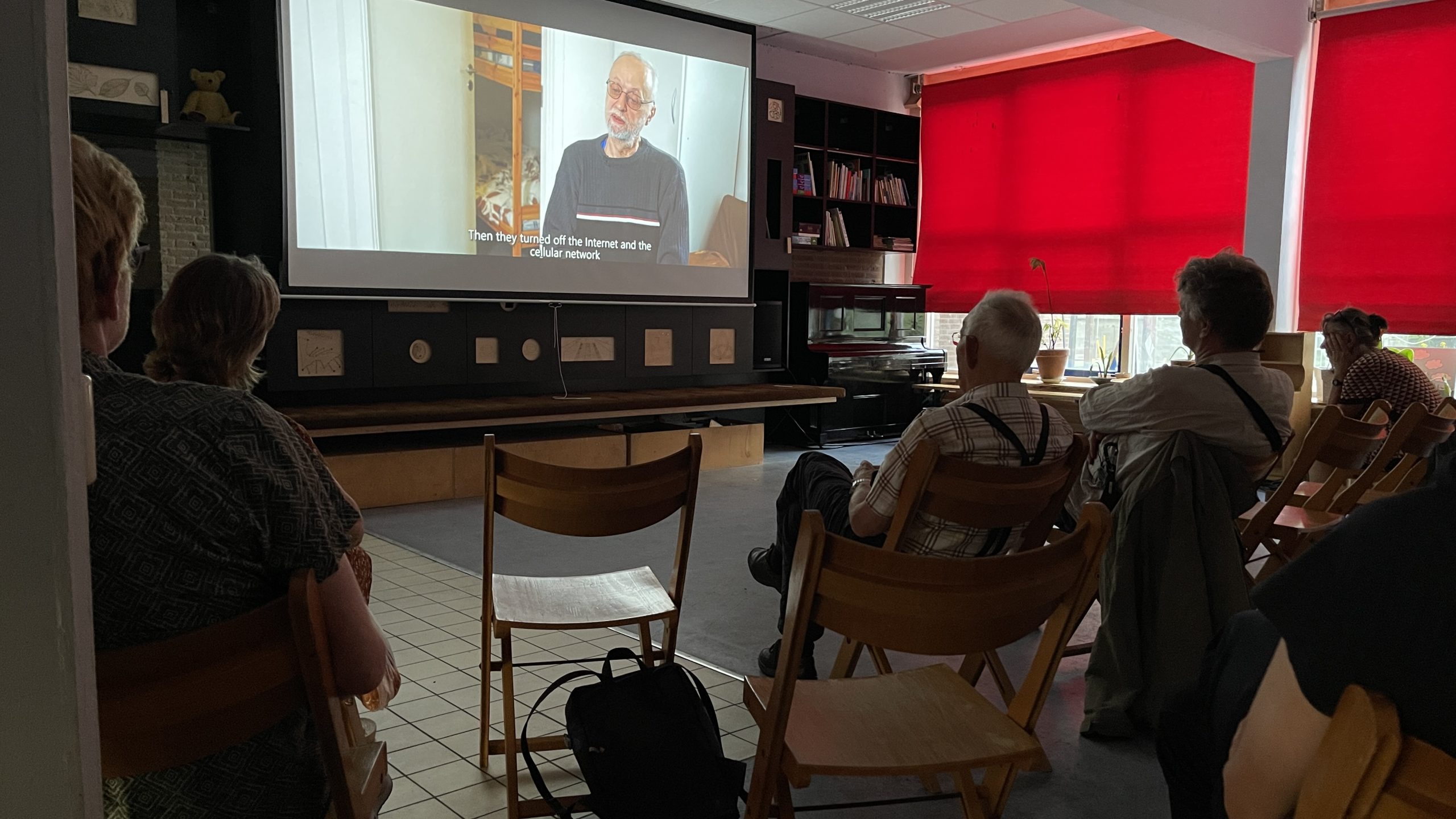

It all started after we watched the film, and understood that it’s about the war through the eyes of ordinary people. “Mariupol. Unlost hope” introduces five city dwellers, who calmly and without fear tell what they saw, felt, did, and thought in Mariupol in the first month of the Russian invasion. It seemed important to us that people in cities “like this” experience these emotions, feel what war is like, and find inside solidarity.

Pont-Audemer (France) / Photo by Nicolas Nithart

So, we held the film’s international premiere on August 24, 2022 worldwide in cities, which were, in our opinion, somehow similar to Mariupol. We had two main criteria for choosing: 1) population; 2) a port and/or industrial, ideally metallurgical, production. Or sister cities of Mariupol. Sometimes we simply looked for an opportunity in a country, even if it was the capital: Geneva or Samoa island in Thailand.

Ilona Shneider, OUP producer, says: “When I first heard about this large project, I was a little bit scared. We had tight deadlines and practically no warm contacts in cities we wanted.”

The campaign organizers mobilized all their “friends of friends” in the selected cities, and also started to write “cold” letters. We found contacts of Ukrainian communities through the Internet. Ilona Schneider recalls that after the first zooms, she was impressed by the willingness to help, from strangers.

“We got the idea: the screening audience should think about themselves, think how would they survive attacks on Hamilton – a city similar to Mariupol,” comments Mary Trach-Holadyk, the vice president of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress in Hamilton. Hamilton was chosen because it is a Canadian center of steel production and the country’s third busiest port with a population of 536,000 (Mariupol had 446,000).

Ukrainian communities around the world joined the project. Vice president of Eastern, Southeast Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania from the Ukrainian World Congress Nataliya Poshyvaylo-Towler says: “I received an email from OUP, they offered to organize a screening. I contacted the board of the Ukrainian community in the Australian state of Victoria, we agreed on time and day. The screening took place on Saturday, August 27, at the Ukrainian Community Center in the city of Melbourne.”

Ilona Shneider: “We waited for the first screenings like it were our birthdays. We cared for everything to be technically perfect, worried how the audience would like the film, we were in touch with the organizers almost 24/7. And it paid off.”

In 2022, the film was screened in Melbourne (Australia), Peter (Australia), Linz (Austria), Baku (Azerbaijan), Tirana (Albania), Varna (Bulgaria), Sofia (Bulgaria), Plymouth (Great Britain), Yerevan (Armenia), Piraeus (Greece), Batumi (Georgia), Tbilisi (Georgia), Ikast (Denmark), Copenhagen (Denmark), Tallinn (Estonia), Herzliya (Israel), Netanya (Israel), Delhi (India), Reykjavik (Iceland), Bilbao (Spain), Savona (Italy), Hamilton (Canada), Beijing (China), Riga (Latvia), Klaipeda (Lithuania), Rotterdam (Netherlands), Utrecht (Netherlands), Dresden (Germany), Leipzig (Germany), Wellington (New Zealand), Auckland (New Zealand), Bergen (Norway), Warsaw (Poland), Lisbon (Portugal), Porto (Portugal), Kosice (Slovakia), Bratislava (Slovakia), New York (USA), Samoa Island (Thailand), Budapest (Hungary), Le Havre (France), Pont-Audemer (France), Zagreb (Croatia), Brno (Czech Republic), Geneva (Switzerland), Gothenburg (Sweden), Stockholm (Sweden).

And the screenings go on.

It touches on a completely different level

Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, a graduate of the Faculty of Physics of Taras Kyiv Shevchenko National University, and now a research associate of the BCMaterials Center in the Basque Country, Viktor Petrenko organized a screening of “Mariupol. Unlost Hope” in Bilbao, Spain. He says that he wanted to show to Basques terrible things happening in Ukraine, to draw the attention of the locals. He made two screenings, one — at the Bilbao School for Refugees for high school students, teachers, parents and alumni, more than 200 viewers, one third Ukrainians, two thirds locals. Viktor Petrenko says that the film made the war more real for Spaniards, who had never experienced such a thing. “Many people could not believe that the war was real and often thought that the news was fake. The film with testimonies of ordinary Mariupol dwellers added credibility to the events. It did not leave anyone indifferent. Locals asked us how they can help and what they can do for Ukraine.”, says Viktor.

If the screening was organized by a Ukrainian community, the majority of the audience was local Ukrainians. In Dresden it gathered a full 90 seats, says Tetiana Ivanchenko, head of Ukrainian House in Dresden, organizer of the Ukrainian Film Days. “It was not just a show, but a session of collective psychotherapy, where people experience their emotions, free them. They look at themselves from above, hear their story told to them by a stranger. But there are no strangers here already, everyone is a friend. With collective pain, collective trauma and a home 2,000 kilometers away.”

At Melbourne, there were approximately 90% Ukrainians and 10% locals. In Varna, Bulgaria, the ratio was 55% Bulgarians, mostly young people, 25% Ukrainians and 10% people of other nationalities. Alina Orlovska, the Ukrainian House in Varna, recalls: «After the screening, there was a deadly silence, broken by sobbing; it lasted for several minutes. Everyone came out with wet eyes, even the men. Some viewers said that they differentially imagined the war in Ukraine. Some discovered “Russian brothers”, and others understood what freedom “Russian world” brings».

Le Havre (France) / Photo by Nicolas Nithart

A Ukrainian girl who watched the film in India says that the movie persuades stronger than the news: “When you read news about Mariupol, see the photos, it touches, but when you watch film, seeing people talking directly from themselves, it touches at an absolutely different level”.

The fact that the film was as close as possible to testimony, without a director’s narrative, worked even more strongly. Iryna Kozik, the First Secretary of the Embassy of Ukraine in the Republic of Bulgaria: “This film tears your soul to pieces, because you understand that it is not the ideas of a director, screenwriter or anyone else. This is reality. This is the reality in which Ukraine lives every day.”

Emotions were at every screening. Nataliya Poshivaylo-Tauler: “People cried, did not want to mingle, discussed. One woman who recently arrived from Mariupol was in the room, many approached and hugged her. She was not in a good condition, crying, trembling.”

Danish viewer: “Extremely powerful, extremely well-made film, very realistic. I have never experienced anything like this in my life. It is difficult to find words to describe what I saw. Everything is so real. So barbaric. It’s worse than I could have imagined.”

About 60 people visited the Leipzig screening, half Ukrainians, half Germans. The organizer Khrystyna Kozlovska, writer, cultural manager, scholarship holder of the German National Library in Leipzig, says that the film is shocking, although it does not contain harsh scenes: “The very fact that people personally and in detail reveal terrible events in their lives, describe the death of loved ones, leaves no one indifferent”

Leipzig (Germany)

Tetyana Ivanchenko: “When I asked several viewers trivial: “What do you think?”’, I heard that documentary strikes. It’s filming pain, fear and evil. Evil that does not have an imaginary face or a hundred hands, so everyday evil. What is scarier than painted, cinematic evil. But it should be shown, it should be talked about — to collect facts, figures and testimonies for the Hague court.”

Flashmob of screenings

Stefané Dalmat organized the screenings in Le Havre, France. He remembers how he told himself that he continues to show the film to as many French as possible when he first saw the audience’s reaction after the screening: “When I watched this documentary, I was ecstatic. Its strength lies precisely in the fact that it only shows reality. Without bias, only the simplicity and unpretentiousness of human stories.”

Then Stefan asked the OUP for a copyright permission to organize screenings on the territory of France. Now, together with two more volunteers, Olga and Nicholas, he communicates with French municipalities, convincing them to organize screenings in their cities. Another task is to find cinemas that could host the event for free. But this small volunteer team is proud to make the mission possible: “Paris screening for the mayor and the members of the city council would be a great victory for us. We are working on it and do not lose hope.” Stefan proactively promotes the film and helps with screenings to everybody interested, for example, a professor of history from the University of Cannes, who wants to show “Mariupol” to his students. “I gladly accepted his offer, because young people are an audience I want to pay special attention to. The more they are informed about the real situation, the more they will be able to analyze information and separate truth from propaganda,” Stefan believes.

Pont-Audemer (France) / Photo by Nicolas Nithart

After the Brno screening at the Vesna women’s educational society, we received two more requests: from the Brno Higher Specialized School (VOŠ) for students and from the community of the city of Breslau. Kateryna Samokisha, the curator of the exhibition “Ukraine. Cost of freedom” in New Zealand’s Auckland Museum, says that the film impressed New Zealanders, and the managers of the museum asked to do another screening, specially for the staff.

So, the screenings became a flash mob.

Iryna Kozik: “After the Embassy announced the screening in Varna, we got a lot of questions about a screening in Sofia. So, we decided to show this film in the Bulgarian capital. It’s great that almost everyone at the Sofia screening were Bulgarians. They knew that the film was not a light-hearted one, but still came. No one left the room until the end, no one! The audience was speechless. It was one of the most shocking post-movie silences I’ve ever heard. Reviews appeared later, when people recovered and began to express their opinions on social networks and in articles in the Bulgarian media.”

The empathy campaign was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. The Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba called these screenings a part of the public diplomacy of the Ministry, and emphasized that such humanitarian projects make it possible to reach the hearts of people around the globe.

Mary Trach-Holadyk: “When the movie ended, people sat quietly until I started saying words of gratitude. Then they approached me and asked how they could help. People were very moved, they cried, they could not believe that such a thing was possible in our time. The film discovered everyone the fear of war… the feeling we have never experienced. And it showed the things the world must see! I would like to show this film again.”

Pont-Audemer (France) / Photo by Nicolas Nithart

“How can this happen in Europe today?”

Marieke Hillen from Rotterdam city center Het Wijkpaleis wrote to the Organization of Ukrainian Producers after the screening in Rotterdam: «We had a nice post-discussion moderated by NRC journalist Mark Duursmi. “What should the world do now? What do we all need to learn?” — asked the viewers. I believe that the Netherlands, and perhaps the whole Western Europe, should learn to make more choices from an ethical point of view, not only from a business perspective.» Marieke mentioned a “cynical photo” — King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands drinking with Putin at the Olympics in Sochi. «In the end, we came up with a question that we didn’t answer that evening, but that we all “took home”: how can we make Ukraine stay in the news, so the world continues to sympathize. That it does not fall into apathy, but feels this war as our own?», Marieke says. «After the movie ended, we had a deadly silence, broken by sobbing; it lasted several minutes. Everyone came out with wet eyes, even men. Some viewers said that they differently imagined the war in Ukraine. Some discovered “Russian brothers”, and others understood what kind of freedom “Russian world” brings».

Rotterdam

Not to let the world forget about the war — that was the motivation also for the organizers of New York screening. Tatyana Overina, PR & Communication strategist, PowerUp, NYC: “I really wanted to bring American journalists and American audiences to the screening. After the film, we organized a public discussion with representatives of American intellectual elite.” The screening took place on November 1 in Manhattan, in the fashionable modern complex Scandinavia House in a hall for 170 people. “A few days before the event, the tickets were sold out, and some people could not get there. The film made a very strong impression. People cried. Many of the viewers later said that they could not even imagine how terrible the war events were. After the film, we had a panel discussion. It was also exciting, the audience did not want to leave, they approached the panel speakers and continued the conversation”, recalls Tatiana.

Kateryna Samokisha watched the film three times and says that she cried every time: “This film is not just about the war, it is about the genocide of our people, that our land is once again experiencing. At the same time, this is a film about resilience and faith in the impossible, about salvation and invincibility.”

New York

Nataliya Poshyvaylo-Towler admits that people in her Australian community are still talking about the film. Khrystyna Kozlovska says that after the film, people asked if a sequel will be.

So, there will be a sequel. The second OUP film from the cycle about Mariupol is currently in its editing stage. It is called “Mariupol. Occupation”, and it tells about the time when Mariupol was under the Russian occupation. The same crew that made “Unlost Hope” is working on it.

By the way, a group of volunteer translators from the TED project wrote to the OUP and offered free help in translating new film subtitles. And this also happened after “Mariupol. Unlost hope”.

Olga Vaganova, Organization of Ukrainian Producers, specially for NV